(Editor’s note: On Monday, Feb. 1, the World Health Organization declared the cases of microcephaly believed to be associated with the spread of the Zika virus to be a public health emergency of international concern — a designation reserved for an “extraordinary event” that is “serious, unusual or unexpected.”)

By DR. KRIS BRYANT

Another virus is grabbing headlines.

Only a year ago, the news was dominated by reports of Ebola virus, and the World Health Organization kept a running tally of cases in West Africa. Now attention has shifted half-way around the world, as Zika virus spreads through Central and South America.

Compared to Ebola, Zika is a wimpy virus. Only one in five people infected actually get sick. Symptoms include fever, rash, joint pains and red eyes. Nearly everyone recovers. Nevertheless, The Guardian reported on January 30 that some experts are calling Zika virus an even greater potential threat to global health than Ebola—and that virus killed more than 11,000 people.

Zika infection occurs after the bite of an Aedes mosquito. Unlike Ebola, whose victims were isolated to prevent spread to others, Zika is rarely transmitted from person to person, with one important exception: women who contract the illness during pregnancy can transmit the infection to their unborn infants. Now there is mounting evidence that fetal exposure to the virus can results in birth defects. Coincident with outbreaks of Zika in Brazil and French Polynesia, there was sharp increase in babies born with abnormally small heads or microcephaly.

The virus has been detected in amniotic fluid samples from two pregnant women whose fetuses were found to have microcephaly by prenatal ultrasound. Zika virus genetic material was also recovered from multiple body tissues, including the brain, of a microcephalic infant who died shortly after birth. The WHO notes the link between Zika virus infection and birth defects “has not been established, but is strongly suspected.”

Earlier today, WHO Director-General Margaret Chan convened a Health Regulations Emergency Committee on Zika virus. The Committee’s charge was to determine whether the outbreak constitutes a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern[Office1] .”

Earlier today, WHO Director-General Margaret Chan convened a Health Regulations Emergency Committee on Zika virus. The Committee’s charge was to determine whether the outbreak constitutes a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern[Office1] .”

Seriously?

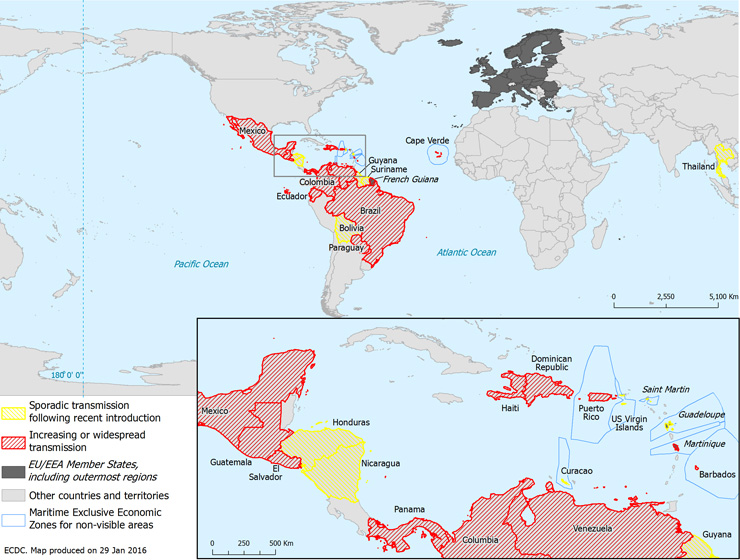

As of this post, the virus has spread to 27 countries and regions. At this time, there are no vaccines available to prevent infection, and no effective treatment once infection occurs.

The United States Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention has recommended that pregnant women consider postponing travel to the areas where Zika virus transmission is ongoing. Pregnant women who do travel to one of these areas are urged to talk to their doctors or other healthcare providers first and strictly follow steps to avoid mosquito bites during the trip. Women trying to become pregnant or who are thinking about becoming pregnant are also advised to consult with their healthcare providers before traveling to these areas and strictly follow steps to prevent mosquito bites during the trip.

“I’m not pregnant and I’m not lucky enough to have a vacation planned to Central or South America. Do I even need to worry about Zika virus?” a friend in France recently asked me.

According to the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, there have been no cases of Zika virus originating in Europe to date, and imported cases are rare. The ECDC calls Zika “an emerging infectious disease with the potential to spread to new areas where the Aedes mosquito vector is present.”

Roughly translated, that seems to mean “it could happen here, even though right now it seems not very likely.” A variety of the Aedes mosquito is found in Europe, primarily around the Mediterranean, but fortunately, transmission of dengue and chikungunya, two other viruses carried by the same insect, is still very uncommon.

The ECDC acknowledges there could be “onward transmission,” as individuals infected with the virus travel to or return to Europe. Infection could spread if the right kind of mosquito bites an infected person and then bites someone else, transferring a tiny amount of the virus-contaminated blood. If there is a bright spot, it’s that the virus only stays in the blood of an infected person for a few days to a week. It is also fortunate that mosquitoes are not very active in the winter in most parts of Europe.

Still, avoiding mosquito bites, wherever you are in the world, is a good idea. Zika virus aside, mosquitoes can cause a long list of diseases, including malaria, West Nile virus, yellow fever, dengue, chickungunya, Japanese encephalitis virus and many others.

So look around the areas where you live and work. Eliminate any collections of standing water, as these can be mosquito breeding grounds. Wear long-sleeved shirts, long pants and socks. To enhance protection, treat clothing with permethrin or purchase pre-treated clothing. Apply insect repellant to exposed skin, especially during hours of highest mosquito activity. Zika-carrying mosquitos bite during the day or dawn to dusk. Malaria-carrying mosquitos bite at night, or dusk to dawn. The CDC also urges individuals to “Use common sense. Reapply repellents as protection wanes and mosquitoes start to bite.”

Let’s hope common sense also prevails as the WHO considers “next steps” in the battle to control the spread of Zika virus.

About the author: Dr. Kris Bryant is a pediatric infectious disease specialist practicing in Louisville, Kentucky.