(Editor’s note: This is Pt. 1 of a continuing series documenting the work of a multi-lingual Ukrainian expat in Berlin helping newly arrived Ukrainian refugees.)

They still arrive.

Women with and without children. Old couples. Mothers and daughters, mothers and sons, grandmas and grandkids, sometimes with dogs and cats in tow. Some travel with a purpose; those who have relatives or friends who can host them.

Some only know the country they want.

“I am going to Belgium,” a young woman tells me.

“Why?” I ask, because we’re in Germany, which many people choose for its social support (the support that is pretty lame if you ask me, but some countries don’t have any, so … what do I know?)

“I heard it’s good there.”

I shut up, because who knows where the good is, and what is even good for a person who had to flee her country and probably left some loved ones behind?

I direct her to the travel center where they give free tickets to people with Ukrainian passports. I go out of the tent with her and show her the way; it’s just into the train station and one floor up. They even have a separate line for Ukrainian refugees now.

Shining a light in the darkness

I am on a translation shift in the tent belonging to the Berliner Stadtmission, which provides a bus to transfer the Ukrainian refugees to an arrival center in Berlin Tegel. They built a huge tent in front of Hauptbahnhof — the train station — for people to have some place to wait for the bus. There’s a food and drinks section in the corner, a children’s corner with toys, books and crayons, where some volunteers watch over the children while harried mothers can grab a bowl of soup or a sandwich and coffee. There’s a station where people can get some hygienic products, like diapers, wet tissues, menstrual pads.

There’s another volunteer center for Ukrainian refugees in the train station itself; they work independently and provide approximately the same services, except the list of products they offer is, I think, bigger. They have shampoo, soap, shaving foam to hand over; they also collect small toys to give to the kids who weren’t able to bring any, and they collect the over-the-counter medicine supplies which people can buy and bring over.

As far as I know, they aren’t coming from any organizations; they self-organized way earlier than Berliner Stadtmission appeared on the scene, so in some ways, they have a better infrastructure. They have a list of products they need online, the list is regularly updated and a person can sign up for some items there, and just buy them and bring to the station. There’s also a list of Telegram channels for all the train stations in Berlin where volunteers set up their centers, so one can find out details about the current situation and needs.

I haven’t yet worked in that center, though it’s probably the next thing on my list. Today, we’re helping in the Berliner Stadtmission tent.

Divisions of labor

I registered online and got a QR code, so I use it to check-in and then a Berliner Stadtmission employee gives me an orientation talk. Before it’s over, I am already pulled away by someone. I nod to the coordinator and go with the person. He needs a train ticket; that’s something we know how to do.

“It’s not your task to fulfill their needs,” the coordinators warned me. “It’s your task to translate. If you don’t know how to solve the request, direct them to the people in blue vests; if people in blue vests can’t speak with them directly, you translate.”

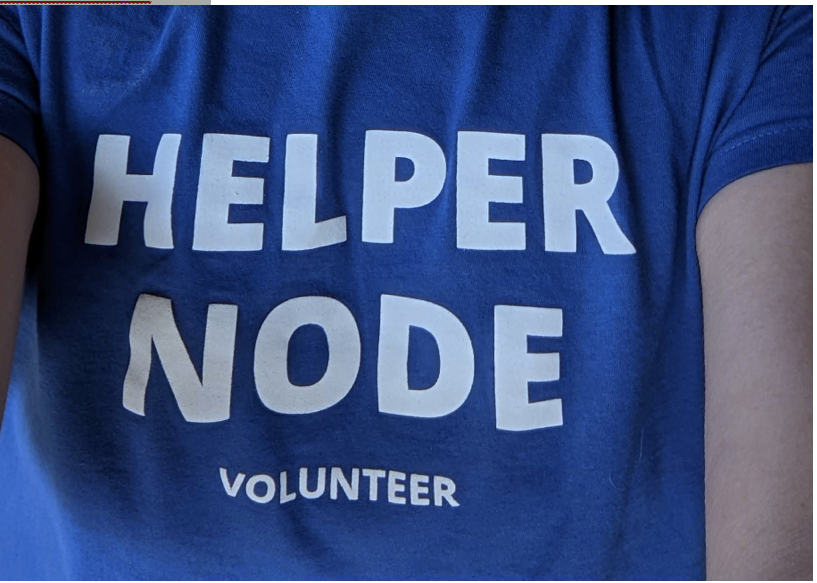

People in blue vests are from the Berliner Stadtmission; they’re employees, not volunteers. Everyone in the tent has a color-coded vest. Blue are Berliner Stadtmission coordinators; blue with pink stripes work in the kids’ corner. Green ones are volunteers; green with orange stripes can speak Ukrainian or Russian, they’re on translators duty. I have the orange stripes, though my German is way less than perfect.

But I supplement with English, or quickly use the dictionary to look up the word that’s escaping me.

Most of the blue vests and people from the Red Cross who also have a station there speak good English, so we have at least one common language.

I return to the tent, and look around to see if there’s anyone who needs help with translation. It’s morning, and people arrive slowly. I was already warned that the load will be bigger in the afternoon. But I already see someone else who just entered and is looking lost.

I am on my way.

See more about the Ukraine war in Dispatches’ archives here.

Maryna is a software developer from Ukraine who now lives in Germany. Maryna also writes a programming blog to share her knowledge. She sometimes speaks at conferences, though being an introvert, writing comes more naturally. She says she’s not a professional writer but writing is something she likes, “and I think I can do it pretty well.”