While culture shock is not a brilliant feeling, it is not necessarily an all-bad thing either. I used to be one of those people who completely dismissed culture shock as a possible explanation for my reactions to moving to a new place. I suppose I did not exactly know what the term entailed and the word “shock” kind of threw me off.

It may sound, at first, like something that happens to close-minded people who cannot stand coming into contact with customs and ways of life different from theirs. As people who travelled here and there, we find this impossible to take on board: “Of course I am not going through a cultural shock!”

In order to be able to tell whether we all go through cultural shock, we need to understand the real meaning of the concept.

Culture shock doesn’t necessarily feel like a shock

Cultural shock is a “multifaceted experience resulting from numerous stressors occurring in contact with a different culture.” (Winkelman 1994). Cultural shock happens to travellers worldwide whether they are foreign students, business associates, young professionals, or refugees.

Undoubtedly, people experience cultural shock differently depending on many variable factors. In most cases, cultural shock is experienced as a sense of impotence resulting from the perceived difficulty in dealing with an unfamiliar environment.

I found, after loads of research and conversations with more experienced expats, that cultural shock does not necessarily feel like a shock. It actually may manifest itself as an accentuated stress, loneliness, discontent, or it could feel like what happened to me: some problems emerge, which seem new to me, and which I never attributed to cultural issues at all.

I only thought of them as what they were – an unsuccessful professional meeting, an awkward conversation, an outing with friends I do not see eye to eye with, etc.

Here’s the thing: I had the right feelings about the meeting, the conversation, and the outing, but I never attributed these feelings to their true cause. I thought that I am losing my communication skills, and hence the meeting was not great, or that people are not so nice, and hence the outing felt uncomfortable.

Don’t whine – learn from the experience

It turns out that had I contextualized all these experiences in the frame of cultural shock, I would have seen them as things to learn from rather than whine over (not that I don’t recommend whining, I really do. But, like with wine, we need to know when to stop in order to avoid a hangover.)

Back home, I knew quite well how to navigate professional meetings. I also had a very specific understanding of what friendships are like. Naturally, in a different environment, I lost my built-in sensors with which I measure vibes, atmospheres and communication wavelengths.

This is what cultural shock entails: you cannot rely on your instincts and let them automatically, sometimes even unconsciously, guide you through different situations. You actually need to put in a lot of effort which leads to cognitive fatigue. Even if you speak the language, it is not only the words which you need to understand, but also the tone, the volume, facial expressions and gestures.

Funny; not funny

For example, one of the problems I face the most is humor. Humor is quite different from one place to another. However, for me, it was a bit more challenging than it is for others. We Egyptians, among Arab-speaking nations, are known to joke a lot (sometimes when inappropriate, to be honest). If we add to that that the Egyptian sense of humor tends to rely on self deprecation, teasing others, and sometimes looking serious when doing all that, that is a bit too specific.

Now, if we add to that that I am a bit above average, for Egyptians, when it comes to laughing about things, this is a bit “too too specific.”

Finally, take me to a professional context with Portuguese, German, British and French colleagues. Mix that in quite well. You will find me not mixing at all and actually rather floating on the surface. I simply did not know how much humor this mix is capable of taking in in a professional context.

In a non-professional context, it is not always much easier. If I make jokes the way I would back home, I might be perceived by some people as “too sassy” or “tough” when back home I will be described as “friendly” and “inclusive” when making the exact same jokes. Humor is how people who do not know each other bond in my country in order to get over the awkward moments. It is not the kindest sense of humor, maybe. But, the point is that it works there. It does not always work everywhere.

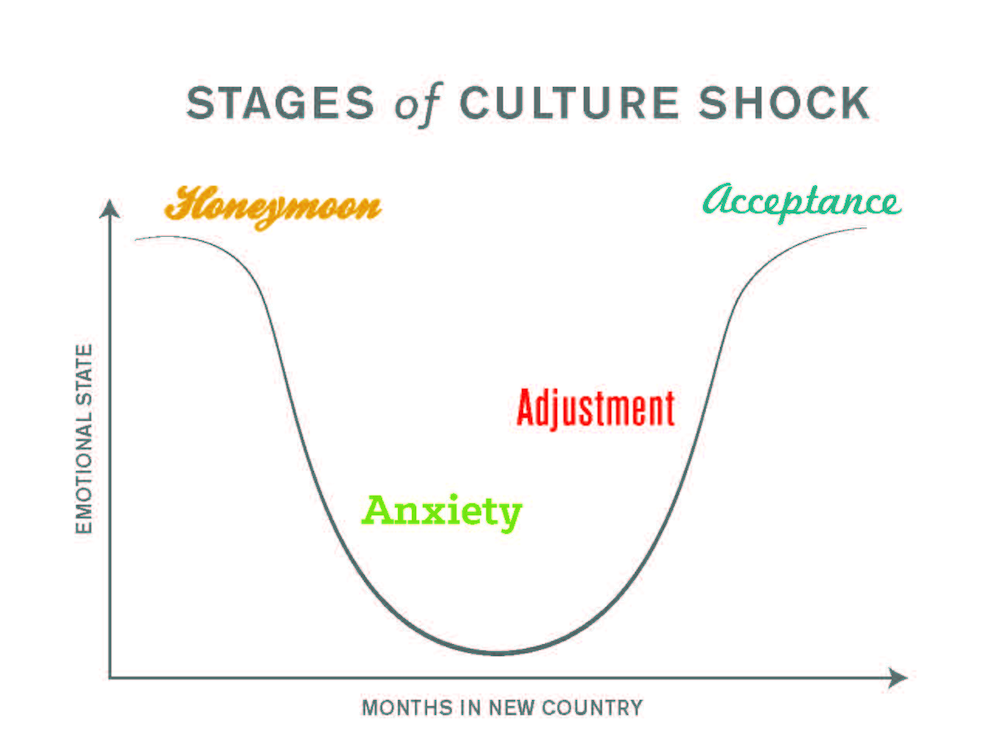

Some literature on cultural shock claims there are four stages of cultural shock:

• the honeymoon phase

• the crisis

• adjustment or negotiation

• adaptation

I do not fully agree with this as it truly varies from one person to another given all range of variables such as: the support system you have in the host country; the activity carried; how different your original culture is from the one you are arriving to. For example: are you a Chinese moving to Lisbon? Or are you a Spanish moving to Lisbon?

Also, financial means make a lot of difference: do you work around the clock to support yourself and/or your family? Or are you comfortable enough to go to an immersive language camp over the weekend?

Therefore, I believe in a more of a cyclical experience where we, as expats, waver between a sense of crises and adjustment. I also do not think that people fully adapt for eternity. Ask yourself this: Do we full adapt in our countries of origin where we grew up, speak the language, have a support system, and know the culture inside out?

I believe that high levels of adaptation are achievable though. I cannot guarantee where my journey will take me, but this is a list of what has worked so far

• Become aware of it

Awareness of the process of cultural shock sometimes suffices to normalize our reactions and decrease hostility towards our new experiences. Try to remind yourself of this process and place your experience into perspective in order to act productively about matters posing a challenge.

- Be a bit prepared

A factor contributing to the sense of stress associated with cultural shock is being away from one’s support system. Changes in personal life are no piece of cake. It is better to manage stress before being overtaken by it. I am good at staying in touch with friends and family back home. I found this to very helpful with stress relief.

Moreover, I have recently worked harder on establishing a social support network in my host country. And it is paying off big time. Something which I have no idea why I never thought of doing was to invest in non-verbal communication channels such as dance or sports groups. My friends who used to go to music jamming nights in bars in Lisbon or to Salsa nights or to football groups got to have a semi-institutional support system which they were immensely grateful for. Now, with the pandemic, I might need to hold on with that one.

- Enjoy More

Problems will arise from immersion in a new environment. We need to expect and accept that. However, what makes it quite bearable is when we create more room for enjoying the experience. Enjoying oneself in a new culture allows for a healthier adjustment and for more tolerance of the emerging challenges.

I said in the beginning that “cultural shock” is not an entirely negative thing. Are not these challenges part of what we left our comfort zones for?

I believe that those of us living abroad are growing in quite different dimensions compared to other dimensions of growth we will be limited to if we stayed back home. It may feel unfamiliar sometimes and we may feel cognitive fatigue other times, but is not that sort of the point?

About the author:

Sarah Nagaty is a PhD researcher of cultural studies in Lisbon. She’s lived in Portugal for two years.

As a student of cultural studies, Sarah is drawn to what connects people from different backgrounds to new cultures and places, how they relate to their new surroundings and what kind of activities they could engage with in their new hometowns.

See all of Sarah’s Dispatches posts here.

See Dispatches’s Lisbon story archive here.

Sarah Nagaty has a PhD in cultural studies, She’s lived in Portugal for six years.

As a student of cultural studies, Sarah is drawn to what connects people from different backgrounds to new cultures and places, how they relate to their new surroundings and what kind of activities they could engage with in their new hometowns.