There is often a lot of debate about the Electoral College anytime a U.S. presidential election looms, but the truth is that so few people – even in the United States – really know much about it (beyond what the media tells them). Hence my European friends often ask me what the deal is and what I think about the system.

The truth is that the history behind the Electoral College is pretty interesting and gives us some insights into how America’s current form of government has traditionally tried to function.

The “real” election

Most Americans are used to national elections happening early in November, which makes sense, since the law stipulates that the actual date should be the “first Tuesday after November 1.” However, regarding the President, the real election happens the “first Monday after the second Wednesday” (yes, it actually says that) in December. This is when electors from each state gather in Washington, D.C. to cast their electoral votes.

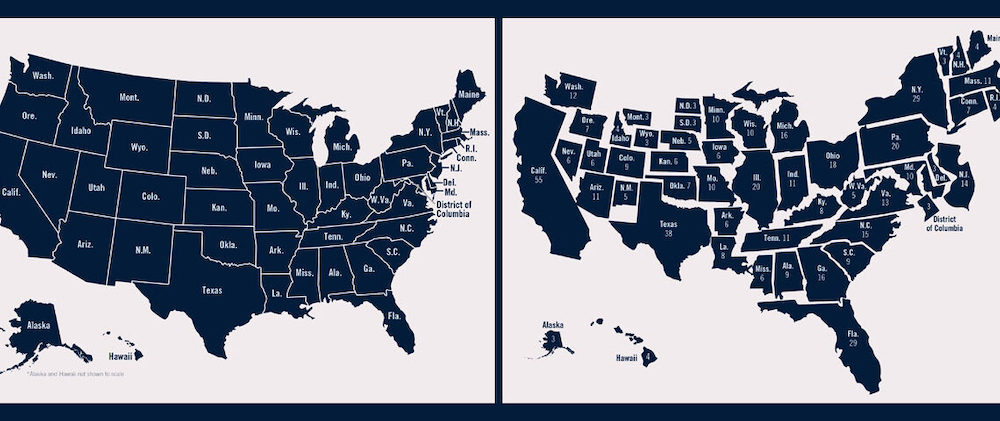

Most states have a winner-take-all system in which the winner of the popular vote gains all the electoral votes of the state. Only Maine and Nebraska are outliers here, allowing electoral votes to go to multiple candidates.

There are 538 electors in total, so 270 is the magic number to win the election this way. A state gets one vote for each senator and representative, so that means the minimum number of votes for any state is three. Most don’t know this, but the District of Columbia, despite lacking statehood, also gets three votes, courtesy of the Twenty-third Amendment to the constitution.

In the case of a tie in the Electoral College, the vote goes to the House of Representatives, with each state having one vote, though a quorum of at least two-thirds of the states must exist for the vote to be valid. If no decision is reached by 20 January, the vice president becomes acting president, and the Senate chooses the vice president. If no choice is made here either, the speaker of the House becomes acting vice-president. This state continues indefinitely until Congress makes a decision. Needless to say, this situation has never unfolded.

Who are the electors?

Actually, almost anyone can be an elector, unless you are a senator, representative, or a holder of “an office of Trust or Profit under the U.S.” This slate of state electors is determined by political parties and, depending on the rules of the party in any given state, it’s not too difficult to become one. There have been some cases of “faithless” electors in the past, i.e. electors who cast a vote for someone other than what their state had ordered, though no faithless electors have ever influenced a presidential election.

How has this worked in history?

Well, there’s been all sorts of interesting cases.

In 1800, there was a tie in the Electoral College between the two candidates for president, which sent the election to the House of Representatives, which chose Thomas Jefferson as president and Aaron Burr as his vice president. To put this in modern terms, for those who do not know this period of American history well, this would have been like making Hillary Clinton vice president for President Donald Trump.

In 1824, no candidate got a majority of the electoral vote (there were four candidates this time, including future President Andrew Jackson), so the election again went to the House, which chose John Quincy Adams as president.

More recently, the complaints in the media and elsewhere have been about the gap between the electoral college and the popular vote (the most famous recent cases are in 2000 – Bush v. Gore – and 2016 – Trump v. Clinton), but these complaints usually come from those who don’t seem to understand how and why the electoral college was instituted in the U.S. and why the U.S. is not like other democracies.

The stock argument is often made that California, with a population of 39.5 million people, “only” has 55 electoral votes, whereas the states of Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, the Dakotas, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont, West Virginia, Wyoming, and of course, the District of Columbia together add up to 37.8 million people, but have 96 votes by comparison.

This argument neatly ignores two problems: a country which has already suffered through a Civil War in the past because of conflicts between state and federal power would not peaceably accept the “right” of California to effectively rule over 21 other states. It also would lead to the practical problem of presidential candidates ignoring everywhere but the major population centers, which would lead to most campaigns happening exclusively in California, New York and Texas, with the rest of the country ignored.

This is not a recipe for civil harmony.

It also implies there is some “standard” form of democracy everyone in the world should be following, when everyone should understand the form of government a people takes on is intimately tied to who they are culturally. The Swiss existed as pure democrats for centuries on the border of the most stable monarchy in Europe: France.

On the other side of Switzerland was the Holy Roman Empire, a “European Union” of its day, with some central power but which devolved many powers to its constituent nations. Why must America follow the lead of European countries, many of whom have forms of governments that were built up and supported by the U.S. and the Marshall Plan?

It’s even more hilarious trying to explain this to French people, whose current form of government – the Fifth Republic – is younger than my mother. America can be chided for its youth in the family of nations (because it is relatively young), but since the U.S. has had its current form of government (its third, following the British Monarchy and the Articles of Confederation), the French have 11 forms of government: five republics, two empires, The Directory, two restorations of the king, and, of course, the Vichy government during World War II or the Free French Forces under General Charles de Gaulle, whichever you prefer to count.

The U.S. has had 45 presidents; has never had a revolution; and transitions just as easily between President Bush to President Obama as from President Obama to President Trump. The Electoral College, like it or not, is part of the stability of that system.

Now, stability isn’t all that matters, and if the American people, rather than talking heads, are interested in changing the electoral process, there is a method to do so: amending the Constitution. But that process is also built on state consensus rather than the whims of major population centers.

The resolution must have a two-thirds majority in both chambers and then goes out to the states (the president has no role in this process) for ratification. If three-quarters of the states ratify (a time limit can be set by Congress), then the amendment becomes law. So, if those who argue for a popular vote to replace the Electoral College “have the votes” of the people, they can certainly get an amendment passed. They’ll just have to make their arguments to more than three states.

Time to vote … for your electors

So, even though those voting in this coming election won’t be voting directly for the president next week, the current system in place ensures that, in effect, the popular vote in each state does determine the president, ensuring all 50 states have a voice, not just two or three of them.

Which would be the case if America moved to a strictly popular vote system.

A version of this article originally appeared on The Gents Blog.

A quick explainer:

• The United States Congress has 535 members – 435 representatives in the House of Representatives and 100 senators.

Congress has two chambers. The Senate has 100 senators – two from each state. This is the more “deliberative” body, with powers to alter legislation originating in the House of Representatives. It also has sole power to ratify treaties and confirm presidential appointees, including cabinet members and top military officials.

The House, which has proportionate representation based on the population of states, is where all tax legislation originates. The House also has the power to impeach officials accused of misdeeds or corruption, and decide elections, as outlined above.

About the author:

Singaporean-born American Stephen Heiner has been living in Paris since 2013, what he hopes to be a permanent home after living in Asia and the United States for most of his life. While he has an undergraduate degree in literature, he also has an MBA, and he’s very much the man who enjoys studying financial statements as much as he enjoys reading essays by G.K. Chesterton or James Howard Kuntsler.

He visits his family in the U.S. and Singapore each year, but in the meantime enjoys his dream city, which he finally had a chance to move to after selling a company he built over a number of years.

You can find him on twitter and instagram @stephenheiner.

You can also follow his immigration journey on www.theamericaninparis.com, where Stephen also offers consulting to those interested in relocating to, and/or making a life in, France.

See more of Stephen’s posts on Dispatches here.