The world of risk capital, like every other mystical culture, has its own jargon, arcane terms and mind-bending concepts. Here’s Dispatches’ handy cheat sheet that will make you sound like you know what you’re talking about so you can go into that next investor meeting and do what we do … dazzle them with bullshit.

(See our 2020 guide to VCs and private equity firms in Europe here.)

Venture capital – Venture capital was invented by a French business genius, Georges Doriot, who never actually worked in Europe, but taught at Harvard. The concept is, you spread risk through an investment fund, then invest in a number of new companies with high growth potential. That relatively small but risky individual investment will improve those companies’ chances of succeeding, turning that investment into a serious amount of money down the line. Doriot’s American Research and Development Corp. proved the concept. ARDC took an early $70,000 investment in Digital Equipment Corp. and turned it into $38 million via an IPO.

Venture capitalists typically raise funds that investors know will be focused on specific categories – tech, social media, fintech or whatever – over 10 years. By and large, VCs only care about two things – market size and the team. They care about market size because in order to get a return for investors, startups must have an almost unlimited potential to extract revenue from virtually everyone on the planet. (See Facebook and Amazon.) They invest in teams because everyone has a great idea, but only a precious few have the organizational ability and merciless drive to build a giant business.

Both VCs and private equity firms get directly involved in guiding startups to success and when they pay off, they pay off bigly. Andreesson Horowitz’s stake in Stack’s recent IPO is worth about $2.6 billion.

Private Equity – Though they often overlap, private equity firms perform an entirely different function. Where the VC invests early to put a promising startup on a growth trajectory toward an exit, PE often looks for private companies that are already fairly mature. PE comes in many flavors, but typically these firms come in and restructure companies by injecting fresh capital and tidying up balance sheets, refining business strategies and bulking up their management. Now, some private equity firms buy and hold, taking long-term fees and profits. But most simply want to take private companies public or to an acquisition, which is a faster track to profits and huge fees.

Limited Partner – So where does all that capital come from? The limited partner is the investor in the VC equation, putting in money in hopes the VC can find a startup that turns into the next Facebook. They’re called “limited” partners because they have little or no say about how the VC invests beyond the initial investment guidelines as to sectors and geographical focus. Limited partners include wealthy investors with high risk tolerance trying to diversify their holdings to institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies as well as family offices, the investment arm of wealthy families.

General Partners – General partners are the founders at VC firms who both have the contacts and powers of persuasion to raise the money from limited partners and the insights and powers of analysis to vet startups and scale-ups. GPs get all the credit when the fund knocks the ball out of the park, but take all the blame if the fund goes zero-for-100 and all the investors flee.

Fund “vintage” – Fund vintage is a term that describes where your startup falls on the timeline of a VC’s 10-year fund. If you’re at the beginning, you get a lot more latitude because the pressure to get an exit isn’t as great. As the fund matures, the pressure to make money for investors increases while the time to do it in decreases.

Exit – An exit occurs when a new company is acquired or goes public and investors get back their principal along with an obscene profit. Or at least a modest profit, you never know.

IPO – There are two ways risk investors typically have an exit: through the company they invest in getting acquired, or through an initial public offering when a company “goes public” and gets listed on a public stock exchange.

Liquidity event – Liquidity event is a fancy way of saying an investor scored big with an exit. Which, of course, makes that person a target for every general partner who’s raising a new fund.

Deal flow – VCs and PE firms need constant opportunities to make money for their investors. But as the risk investment world becomes more fragmented, opportunities to invest in worthy startups and scale-ups, or “deal flow,” become few and far between, which is shifting the balance of power to entrepreneurs.

The Valley – This is shorthand for Silicon Valley, an area of Northern California roughly the size of the Netherlands running from San Francisco south to San Jose. It’s home to most of the most innovative companies in the world including Apple, Intel, Facebook and Google.

Every European city claims to be “the Next Silicon Valley,” but none has the essential foundation of a great engineering university producing entrepreneurial talent (Stanford) and a concentration of risk capital (Sand Hill Road) willing to invest in that talent.

Sand Hill Road – This road runs a few miles from Woodside to Menlo Park near Stanford University in The Valley and is home to the most prestigious and successful venture capital firms in the world, including Kleiner Perkins, Greylock Partners, Sequoia Capital and Benchmark. This is the crucial startup ecosystem component missing in Europe.

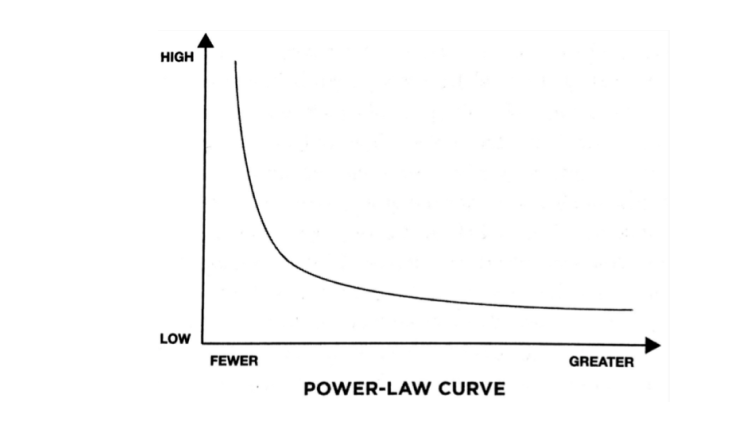

Power Law Curve – The whole VC thing looks so cool, but in reality, it’s a sucky way to make a buck. Why? Because a tiny minority of elite firms reap the vast majority of profits from early-stage investments in huge winners such as Facebook and Google. And of course, the better those marquee firms such as a16z and Sequoia Capital do, the less likely limited partners are to invest in new VCs trying to raise their first funds, and the less likely that emerging VC firm is to see the most promising startups.

All this can be reduced to a nifty power law curve so popular in the statistics world, with the successful VCs on the far left and everyone else on the right side of the chart.

Unicorns: Unicorns are startups with $1 billion valuations or capitalization. Unicorns are a dime a dozen in the US, but sightings in Europe are rare. European tech Unicorns including Klarna, Transferwise, Deliveroo, Blablacar and Revolut.

Required reading (there will be a quiz)

“Secrets of Sand Hill Road” by Scott Kupor, a venture capitalist at Andreesson Horowitz.

To really understand Kleiner Perkins and the VC world: “The New New Thing,” by Michael Lewis, who also wrote “The Big Short.”

“Why Software is Eating the World,” by Marc Andreesson.