After studying the history of art and architecture of Sicily for two weeks in Taormina, I was excited to set out and visit the rich mix of UNESCO world heritage sites and other ancient, medieval and baroque cities and structures we covered in class.

As one local Taormanese told me, “Sicily is an island with nine fathers.” Indeed, after being settled or ruled by the Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, Svevi, Goths, Normans, and Spanish, Sicily is a magical repository of languages, foods, plants, art, architecture and people.

VALLEY OF THE TEMPLES, SICILY (All photos by Nancy Church)

On my list to visit were Palermo first, then Monreale, the Greek temples of Agrigento, Piazza Armerina, Modica, Ragusa, Noto and Catania. I admit I was slightly reluctant to visit Palermo alone, but once there, I ended up loving it and adding two days to my stay.

What I discovered, in addition to stunning churches and museums, was a cultural capital with an artsy vibe, full of neighborhoods (quartiere) with fresh markets or street food during the day and bustling piazzas and restaurants at night.

A SIDE OF PALERMO YOU MUST NOT MISS

And, thanks to an anti-mafia movement that promotes both “critical consumerism” – patronizing only establishments that have declared and proven freedom from mafia extortion – and a renewed sense of dignity, I saw a side of Palermo I might not have noticed: a sampling of proud, dignified, defiant, fearless proprietors, volunteers and citizens.

The highlight of my time in Palermo – including seeing Turandot in Europe’s third largest opera house, and Antonello di Messina’s “L’Annunziata” at Palazzo Abatellis – and one that informed the remainder of my time there, was a private “No Mafia” walking tour.

Curious at first whether I’d be led to secret, speakeasy-type doors or to see scenes of past mafia crimes to hear stories of gore and violence, or to learn about a movement of determined citizens, I signed up as soon as I heard about it at the MICRO² tourist office in the Kalsa district just north of the train station.

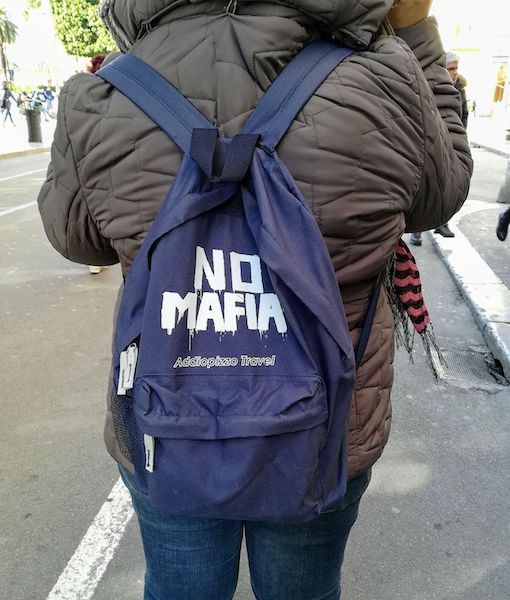

What I experienced with the No Mafia tour was a peek into the soul of a city, its people and a grass-roots movement fighting an indignity they have not only suffered but many, sadly, have come to accept over the years. Our meeting point was Piazza Verdi, in front of majestic Teatro Massimo. I spotted my guide, Linda, by her blue backpack with “NO MAFIA” in large white letters (more about that later).

Linda began by explaining why we start at the steps of the Teatro Massimo, featured in the final scene of “The Godfather Part 3”:

The theatre is a metaphor for the town itself: the eradication of stereotypes linked to Sicily and mafia can start from here. Thanks to “The Godfather,” this theatre became in the world the symbol of a territory entirely agreeing with the mafia. However, it was this theatre that in 2000 hosted the opening ceremony of the international conference on transnational organized crime, convened by then-UN Secretary, Kofi Annan, showing the world a territory united in fighting against the oppression of the mafia.

She then explained the “Addiopizzo” movement and how its member organizations defy the mafia and no longer pay the pizzo, the extortion of money exacted by Cosa nostra of merchants, restaurants and other institutions.

But it’s not just about defiance, it’s about dignity, as stated in a foundational statement of the association:

“An entire people who pay the pizzo is a people without dignity.” Un intero popolo che paga il pizzo è un popolo senza dignità.

She showed me the Addiopizzo app, which helps users practice “critical consumerism” and lists the nearly 1,000 shops and restaurants that have enlisted – after rigorous financial scrutiny – to join the Addiopizzo movement.

We then set off to meet a member merchant and visit markets and memorials. I did not expect to discover a sense of pride, of renewal, of defiance and of commitment to upholding an anti-racket, anti-mafia way of doing business.

Our first stop was Tanto di Coppola, a shop for the famous “coppola” hat originally worn by contadini (farmers), and later co-opted by mafiosi who tilted the hat (called “coppola storta”) to indicate their status as a menacing extortionist.

The beautiful men’s and women’s hats (and small purses and scarves) in this store are handmade my women in a nearby town who are victims of the mafia or are at risk from the mafia.

NO FEAR

It’s interesting that the workshop where these women work is across the street from the house of one of the biggest mafia bosses in Sicily, a proverbial snub of the nose (or perhaps a more profane gesture) if ever there was one.

The shop clerk and my guide recounted stories of how the mafia intimidate and extort, but further explained that for years now, an increasing number of merchants have refused to pay the pizzo.

Some have suffered dire repercussions, others find patrons stop shopping at these merchants for fear the mafia will take note and hurt them somehow.

However, thanks to a 4×4-inch Addiopizzo window sticker and the app, others only patronize these establishments as I did after the tour.

We then walked through the Mercato del Capo farmers market on the way to the Piazza della Memoria, site of a tribute to 11 justices from Palermo and Trapani who were murdered by the mafia between 1971 and 1992. Two years ago at language school in Bologna, we studied the heroic and lasting anti-mafia practices of two of these national heroes, Justices Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, both murdered in 1992.

I recall the sadness and nostalgia with which our instructor told us about these two sons of Palermo who managed to bring down hundreds and hundreds of mafiosi. My guide, Linda, added to the history lesson by telling me that the FBI in the U.S. still uses some of the methods established by Giovanni Falcone to fight the U.S. mafia.

PIAZZA DELLA MEMORIA

Our next stop was a surprise, one we stumbled upon in a tiny street while admiring brightly painted carriages in the traditional style of the Palermo “opera of puppets.”

Linda knew of the artist but had never met him. We turned around to find him painting in his studio, a garage-type space that housed room after room of his hand-painted theater screens, barrels, and many collector items.

He invited us to the back room to show us his family’s 170-year-old puppets: It turns out he is a fifth-generation puppeteer. He kindly demonstrated how to work one of the heavy, 1/3-scale puppets by manipulating the arms, clinking the tiny swords and shields.

He beamed with pride and gave me a CD detailing the history of his family and the puppet opera tradition. I left a small unsolicited donation in a nod to support this precious tradition.

THE CHURCH IS PART OF THE EFFORT

Meeting this artist was merely a fortunate coincidence (this stop is not on the No Mafia tour). Back out on the street, Linda continued the tour by explaining the legend of the “Beati Paoli” – a secretive sect that began in feudal times to defend commoners – and various rituals the mafiosi use in emulating this ancient order.

We then headed to the 12th-century cathedral of Palermo, which served merely as backdrop for a brief history of the Catholic church’s tacit sanctions of mafia behavior. The guide made clear, however, there are, in fact, heroic priests and nuns who choose to go into schools in poverty-stricken mafia strongholds to educate children and adults, to help them escape the grip of indignity imposed by lack of education and opportunity.

I related this to how other terrorist organizations gain a foothold.

We ended in front of the future Antimafia Memorial Museum where Linda invited me upon my return to Palermo to visit the highway memorial site of the car bombing that killed Giovanni Falcone and his associates in 1992.

She explained the origin of the “No Mafia” logo on her backpack and on the sign hanging over the door in front of us. Immediately after the bombing, a citizen painted “No Mafia” on the side of a nearby metal utility cabinet, one that faced the home of a mafia boss up the hill.

She explained the origin of the “No Mafia” logo on her backpack and on the sign hanging over the door in front of us. Immediately after the bombing, a citizen painted “No Mafia” on the side of a nearby metal utility cabinet, one that faced the home of a mafia boss up the hill.

The utility then painted over the words. The citizen repainted the words … and so on for several repaints until the utility finally left the words, which remain today.

I also learned about how the government is expropriating mafia property and turning the proceeds over to victims. And, immigrant shop and restaurant owners have joined the Addiopizzo movement.

Staying in Palermo two extra days meant nixing Modica, Ragusa and Noto from my itinerary. However, I fell hard for Palermo and Sicily, so there will definitely be a next time.

[It is easy and inexpensive to reach Sicily. I flew Volotea airlines from Verona to Catania for less than 40€ one-way, including luggage.]

About the author:

Nancy Church developed wanderlust at the age of 10, which fed her love of languages and led her to study French, then Italian. A world nomad, she lived in Bahrain and has since traveled to 26 countries.

Nancy Church developed wanderlust at the age of 10, which fed her love of languages and led her to study French, then Italian. A world nomad, she lived in Bahrain and has since traveled to 26 countries.

An MBA, her career includes 25 years in product development and marketing in the financial services industry, for firms including Ernst & Young. Before retiring in 2017 to travel extensively, Nancy worked for the U.S. Green Building Council, promoting sustainable buildings and smart growth.

When not in her hometown of Louisville, Ky., she enjoys exploring and hiking in Europe, and visiting with friends she has made in her travels.