Greece is a very popular holiday destination and if you visit it, you’ll understand why. It has blue skies, deep blue and turquoise seas, mountains, forests, lakes and friendly people. Greeks pride themselves on their hospitality and love of strangers or foreigners, and they even have a word for this, φιλοξενία (philoxenia).

But who are the Greeks? And what are they like when you live here and speak the language?

One example I can give of this is when some young friends had their money and passports stolen on the Athens metro at night. They went to report the loss to the police, who were singularly unhelpful.

(Tip: The tourist police are so much more cooperative in my experience. They also speak languages other than Greek, which makes for easier communication.)

My friends were sitting on the steps outside the police station and the woman was crying. An elderly Greek woman stopped and asked in impeccable English what was wrong. On hearing their story, she gave them 100 euros so that they could get a room in a hotel for the night.

A true example of φιλοξενία! I wonder if that would happen anywhere else?

Friendly people or mercenaries?

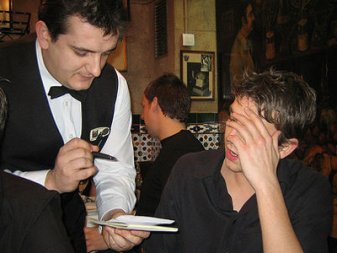

Most visitors to Greece deal with waiters, hoteliers and others working in the tourist industry and generally find them very welcoming. They don’t notice the dollar signs in their eyes. But neither do they understand what is being said about them, on the whole.

Most visitors to Greece deal with waiters, hoteliers and others working in the tourist industry and generally find them very welcoming. They don’t notice the dollar signs in their eyes. But neither do they understand what is being said about them, on the whole.

Let me give you an example:

A hotel owner answered his phone and spoke in English to a guest who had recently left the hotel. She was concerned that she had left her toiletries in her room. The hotel owner was perfectly charming and assured her that her belongings hadn’t been thrown away. She explained that she would pick them up on her way back to Athens airport.

The owner put the phone down and swore profusely, which I found highly amusing.

Who knows what the brand of toiletries was, but the woman obviously put a high value on them, as the journey to the hotel is difficult, and not really on the way to Athens.

She and her husband returned to pick up the items a few days later. The hotel owner was once again perfectly charming, until they had left, when he uttered a string of colourful swear words.

You simply don’t know what Greeks really think of you if you can’t speak the language or understand their body language.

The Greeks are very likable on the whole, but don’t be taken in by those who prey on foreigners; these are called kamaki, or hunters. These are the hustlers who try to steer tourists to tavernas and bars.

Of course, there are Greeks who are genuinely friendly, and I have many Greek friends. They have a wonderful sense of fun and can be relied on to keep a conversation lively.

I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else!

Summer fun can lead to winter blues

It’s one thing being on the islands and the mainland in summer, but in winter, it’s quite different. The friendly waiters go back home, probably to the mainland to face unemployment and few job prospects.

It’s one thing being on the islands and the mainland in summer, but in winter, it’s quite different. The friendly waiters go back home, probably to the mainland to face unemployment and few job prospects.

The islands are almost deserted as Greek tourists also return to the mainland. There is no nightlife, only, perhaps a bar and some cafeneions frequented, usually, by men. Then there may be problems due to bad weather when no boats can get to the islands. Depending on how long the bad weather lasts, there may not be fresh fruit and vegetables, or meat, in the shops.

If it snows, the Greeks will rush out and enthusiastically make snowmen and snowballs. Perhaps unfortunately, snow is rare.

If you live in Athens, or one of the other major cities on the mainland, winter is not so bad. There are entertainment and nightlife, in the form of bouzoukia, which are Greeks nightclubs with live music and performers. You can’t throw plates anymore unless they are plastic.

Instead, women sell carnations for customers to hurl at musicians and singers. Main towns on islands may also have this form of entertainment in winter.

But what if you have your heart set on living on an island all year round?

Choose an island that doesn’t rely on daily or twice weekly ferries to deliver food and other commodities. Naxos is an agricultural island in the Cyclades and is a good place to live all year round. Crete is an excellent island to live on too.

Corfu doesn’t completely close down in winter, especially Corfu town. So keep it in mind. However, it does tend to rain a lot there in winter.

Evia, Greece’s second largest island after Crete, is also open for business in winter, with many people going to its spas in towns like Aedipsos.

If you are thinking of moving to a Greek island it would be best to visit it in winter to discover what it is like. It would be awful if you sold a property in your home country and moved to Greece, only to find that you couldn’t tolerate the winter months.

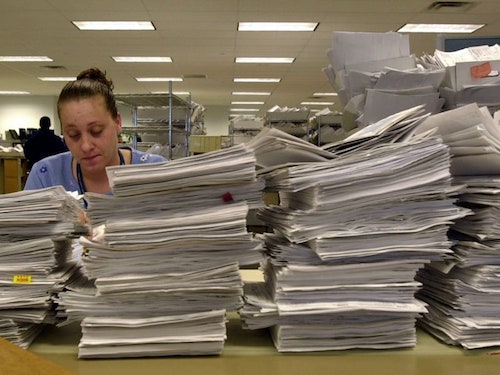

Red tape

When you live in Greece you get used to the ridiculous amount of bureaucracy you encounter. Although public offices have computerized systems now, this doesn’t mean that procedures are streamlined.

When you live in Greece you get used to the ridiculous amount of bureaucracy you encounter. Although public offices have computerized systems now, this doesn’t mean that procedures are streamlined.

You will need to physically be in government offices if you want to get anything done. You can waste more than a day hanging around in them.

Some staff will accept “brown envelopes,” which hurries along your sojourn. Registering a vehicle, applying for a work permit, and a whole barrage of other necessary form filling takes time.

Crying sometimes helps get your case sorted out too. You don’t have to be a wonderful actor to do this. as frustration is bound to kick in sooner or later.

The tax burden

You will need to research the tax laws as they affect you. Most Greeks in employment hire an accountant to sort out their affairs. Since the financial crisis, there have been several tax hikes, which affect the Greek middle classes.

The situation is, however different for ex-pats.

The economic crisis

If you move to Greece, keep your foreign bank account. It will not be subject to the capital controls imposed on Greeks and their bank accounts.

If you move to Greece, keep your foreign bank account. It will not be subject to the capital controls imposed on Greeks and their bank accounts.

The situation seems to be improving now, although there are many people who are unable to pay bills, mortgages and so on. The government has capitulated to European demands and is foreclosing on even first homes now.

Although that means cheaper property prices for those who can afford to buy, it exacerbates the social crisis Greece is seeing.

There are beggars outside supermarkets and on street corners in the cities, and these are not just immigrants, but hard-up Greeks. Some families have been reduced to penury.

If it weren’t for the extended family system, more people would be living on the streets.

Learn the language

Life will be much easier for you if you begin to learn Greek. Start before you get here with videos and audio materials.

Life will be much easier for you if you begin to learn Greek. Start before you get here with videos and audio materials.

You’ll find that Greeks will appreciate your efforts to learn their language. You won’t always be able to find someone to translate for you, so the sooner you begin to learn Greek, the better.

I love living in Greece, but it can be hard to adapt at first. You have to be laid back and just go with the flow. The word “tomorrow” (αύριο pronounced “avrio”) may not mean what you think it means. Think of it more as the Spanish mañana, an indefinite time in the future!

While I love it here, it’s not for everyone.

Holidays are one thing, but actually living in a country is completely different.

About the author:

About the author:

Lynne Evans is originally from Wales but is an inveterate traveller. She is passionate about writing and feels compelled to write something every day.

Lynne has visited many countries in Europe and South Asia. Working as a freelance writer gives her opportunities to travel.

She’s currently living in her favourite country, Greece, in Athens. In the past she was always leaving Greece and then returning. This time she wants to stay, despite the economic situation.

More from Lynne:

Dispatches Detours: Lynne Evans is your guide for where to go, eat and stay in Peloponnese