BY JESSY DE COOKER

Mozart, if you’re a fan. Or fascist pig if you aren’t. It is fair to say that Geert Wilders is probably one of the most divisive figures in Dutch politics at the moment. Call him what you want, but he has some sturdy points that could make The Netherlands a much less international country.

Fourteen. That is currently the magic number right now in the offices of the Partij voor de Vrijheid (Freedom Party in English) at the Binnenhof, the centre of Dutch politics. It is the difference between the current total number of seats held by the party and its leader Geert Wilders in the Tweede Kamer, the Dutch House of Representatives, and their present majority lead in the latest polls. If elections were held today in The Netherlands, the Freedom Party would easily win with 29 seats.

That would give them a lead of three seats over the next in line, the VVD (Liberal Party) of minister-president Mark Rutte. That result wouldn’t come as a complete surprise.

The Dutch have been alienated from the Rutte cabinet. And fair enough, his second term as prime minister of The Netherlands has alway been a rocky one with terror attacks in neighboring Belgium by ISIS, internal bust-ups and the stream of refugees entering Europe and the Low Countries.

The Dutch have been alienated from the Rutte cabinet. And fair enough, his second term as prime minister of The Netherlands has alway been a rocky one with terror attacks in neighboring Belgium by ISIS, internal bust-ups and the stream of refugees entering Europe and the Low Countries.

Reluctantly – and under high pressure from Germany and France – Rutte has welcomed around 50,000 refugees since 1 January 2015. A decision that led Wilders to call Rutte a “friend of terror.” One-liners like this are what have made Wilders so popular among a large part of these unhappy Dutchmen.

He is their spokesperson in parliament.

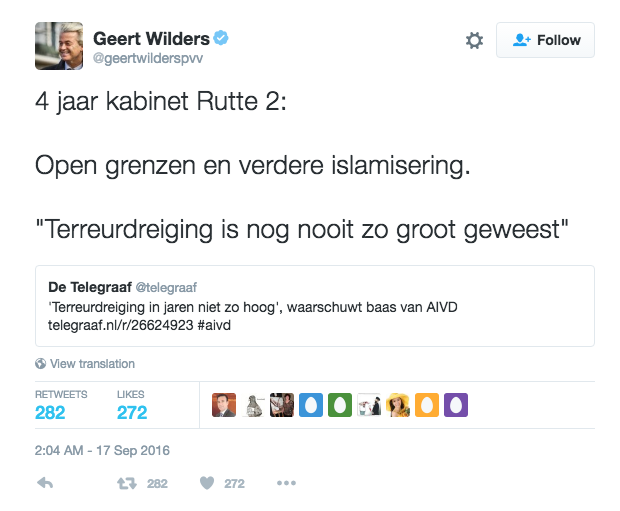

Wilders doesn’t like to fuss about and keeps things simple. He communicates via Twitter and Facebook, and does interviews just when it comes in handy. He has been named the most influential parliamentarian on social media.

Especially via Twitter, he has a great hinterland of followers and is a master when it comes to using 140 characters to their fullest potential. He can confront the Rutte administration on the current safety of the country against terror attacks with a short tweet: “4 years of Rutte II: Open borders and further Islamization. The terror threat hasn’t been as great as now.”

If you think that’s brief, you will be surprised to see the concept plan his party has prepared for the moment when they win the coming Dutch elections in March next year.

In The Netherlands it is common for political parties to release concepts of their ideas as sort of early promises leading up to elections. The Freedom Party of Wilders was one of the first to start the cycle to the Torentje, the symbolic residence of our minister-president. And they went for quick and compact, just as Wilders’ strategy on Twitter. They managed to distill their ideas to the size of one sheet of A4-paper.

Next to nothing when you compare it to the 147-page document of D66 (Democrats’66).

In the plan, called “Netherlands for us again,” Wilders portrays himself as Don Quixote against the “Islamization of The Netherlands.”

“Enough of mass-immigration, terror and insecurity. Instead of financing the whole world and people we don’t want here, we’ll spend our money only on the common Dutchman,” the introduction reads. What follows are eleven points the Freedom Party will address when they come to power.

The first three themes are the most eye-catching:

- De-islamize The Netherlands

- As an independent country, we’ll leave the European Union

- Direct democracy: People get power through binding referenda

First, with de-Islamizing The Netherlands, Wilders’ party wants to close theborders to all immigrants from Islamic countries, forbid women to wear traditional hijabs in public functions and – last but not least – close all mosques and Islamic schools. Oh, and he wants to forbid the Quran. Basically, he wants to shackle nearly a million Muslims in The Netherlands by forbidding them to practice their religion.

Think of the international scrutiny he will face when he starts closing houses of prayer, although it won’t make him doubt himself. He sees himself as the sole guardian against Islam since 1998, a fellow politician told me when I profiled Wilders for HP/De Tijd, a Dutch opinion magazine.

Second, Wilders wants to perform a Nexit, a Dutch exit from the European Union. He has been crying out for this since 2012. Back then, he said being a member of the EU would mean “we can’t defend our own identity and tackle the problem of Islam.” Lexit will also give back the Dutch treasury billions of euros in membership fees. At least that was the conclusion of research … commissioned by Wilders and his party.

Third, being the populist politician he is means you can be the voice of the people (Populus in Latin). But Wilders also wants to give a certain power to these people by organizing binding referenda. This is an idea he saw in Switzerland, where the Swiss can blow the whistle on their leaders with these referenda.

Last April, during the Ukraine Referendum we saw the effect it can have on the Dutch. About 2.5 million people voted against the Association Agreement between Ukraine and the EU. It left the Rutte administration to blushingly return to Brussels, as a no vote by The Netherlands meant the agreement was put on hold. Wilders didn’t gain much as he didn’t lead the no-campaign, but it still made Rutte look bad.

“He is the personification of a hardened Dutch society,” a lawyer and close ally Theo Hiddema told me for the profile for HP/De Tijd. Wilders’ statements mean he has been living in safe houses for years. But it doesn’t change his ways. “His way of politics is based around fear and anxiety,” a former ally Bart Jan Spruyt said. “If the EU in its current state isn’t right, we have to leave it immediately. And when Muslims aren’t integrating in this country he wants to pester them or send them back. He doesn’t believe in political solutions to problems.”

A minister-president in The Netherlands should be the face of our country and if we are to believe Wilders, he will restore our Dutch values. His concept plan provides the first outline of how things will be in his Holland. The current political arena in The Netherlands, with a weak minister-president Rutte and a scattered array of parties, is ideal for his type of politics.

There hasn’t been a political party with the all-out majority since the 19th century, offering a ray of hope to those not supporting Wilders’ brand of politics. In the current Dutch voting system, parliament is divided by proportionality, so the winner of the election has to form a coalition, which usually curves the sharp edges of plans.

For expats, the question is, will the ejection of Egyptian or American Muslims whose technical skills are vital to their companies be a possibility in The Netherlands of the future? Probably not, because the political parties with whom Wilders has to collaborate won’t be easy to persuade on these points.

Rutte has called for extremist Erdogan supporters who attacked a journalist to go away or to “pleur op” in Dutch. But Rutte added he would never force hard-working citizens (no matter their nationality or religion) to leave the country.

No other Dutch political parties have statements as tough as the Freedom Party. And rather than surviving, the first idea of Wilders’ proposed plans will be shot down. No hard working expats will be forced to leave The Netherlands. You are safe in a Wilders’ Holland, although The Netherlands may be a less internationalized country.

Fourteen is his lucky number at the moment, but will Wilders be able to follow through on all his promises? He will need at least 76 of the 150 seats in the Tweede Kamer.

Fourteen is his lucky number at the moment, but will Wilders be able to follow through on all his promises? He will need at least 76 of the 150 seats in the Tweede Kamer.

That is highly unlikely, but his politics and strong points will bring isolation to The Netherlands if he wins in March.

About the author: Jessy de Cooker is a journalist based in Tilburg, Netherlands who covers music and politics.