(Author’s note: I can’t say I never expected to have to sign a contract with France… 🙂 This post about the CIR originally appeared on The American in Paris blog.)

As with many things involving French bureaucracy, when I received my visa vié privée et familial, the process was not truly over. In addition to coming back to pick up my titre de séjour, the administrator told me that I’d be summoned by l’Office Français de l’Immigration et de l’Intégration (the French immigration and integration service, or OFII) to sign a contract d’intégration républicaine, or CIR, have a language proficiency interview, and take four days of civic training.

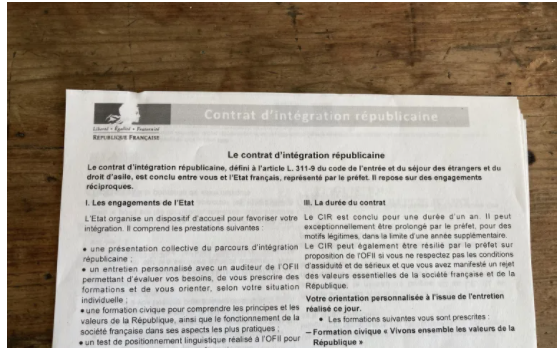

What is a contrat d’intégration républicaine you ask? I wondered the same thing even as I was waiting to sign it.

A CIR is an agreement between any non-European foreigns who wish to live in France permanently and the French government – you’re agreeing to attend the courses on French government, society and culture, as well as attain an A1 proficiency (the lowest level) while they’re agreeing to provide you with language classes, as well as employment and other integration services.

The concept of such an arrangement is very foreign to me, and I’m not sure if any such thing exists in the United States.

The process

The process of my CIR technically begin in October 2020 when I received my visa vié privée et familial; however, I wasn’t summoned by OFII until March 2021. Five months after the appointment, when I was in contact with the prefecture to pick up my new carte de séjour, I mentioned that I hadn’t received a date and they immediately sent one.

Never trust French bureaucracy to function as they say it will — it’s always best to follow up since you’ll still be required to have the paperwork, even if they never sent it.

Once I had the interview scheduled with OFII, I knew there would also be four days of civic training where I learned about France.

There is also an exit interview, which no one mentioned to me throughout the process, and I only discovered when doing research for this post. Since the civic classes are typically scheduled a month apart, and the exit interview is done within three months of completing those, it’s best to assume the entire process will take 6-to-8 months.

OFII Visit

The OFII visit took place at their office in the 13ème arrondissement, a different location from where I’d gone to have my medical exam for my first long-stay visa. No one gave us an official explanation of the afternoon’s agenda or why we’d been summoned, which made the experience even more Kafkaesque. After waiting for what felt like a long time, we were given a basic French proficiency exam which, along with the spoken interview, would assess if we were at least A1 French.

I couldn’t remember the last time I’d taken a written exam, so while it was very easy, it was also surreal. My French is fluent thanks to French classes from middle school through college, a study abroad semester, and my French friends and partner. That said, I don’t have any degrees to prove this (in France or in the U.S.) so the proficiency exam was both required and necessary for my visa.

In fact, in order to have French citizenship, you must have passed a level B1.

After the test was over, we were called one by one for our language interviews. In a moment of foolhardy optimism, I’d left the apartment without a book. Thankfully, I still had a notebook and pen — the wait was so long I wrote my friend back home a letter. When the man who was interviewing me asked what I did, I told him about my writing and he pulled up my website. We talked about literature for quite awhile, and he was clearly pleased to be having a fluent, interesting conversation. Before leaving, we scheduled my first two civic courses at OFII and he printed me convocations for two Fridays in May.

Day One

I arrived for at the OFII office of the 20e arrondissement. It was across the péripherique which I’d always thought meant the address would be outside of Paris and the arrondissement numbering. Enough of us were puzzled by this that we asked the teacher who explained that this street managed to make it “into” Paris while the next block hadn’t.

Like French grammar, there are the rules and there are the exceptions.

The classroom was fluorescent, unpleasant and had tightly sealed windows. None of the 20-or-so other immigrants looked particularly thrilled to be there either. I’d been intrigued by what they’d serve us for lunch but it was a sandwich, apple sauce, and bottled water. I’m not sure why I thought it would be something more interesting.

The day’s lessons were divided into the following sections:

- The Nation: General information about geography, population, economic standing, and government structure

- Health: Emergency phone numbers, health insurance, mutuelles

- Employment: Searching for jobs, national employment agency or pôle emploi, CVs and letter de motivation, starting your own business

- Parenthood: Parental rights, protecting children, types of childcare

- Housing:Types of housing, finding housing, requesting government housing

Since I’ve lived in France for more than three years, most of this information was a review to me, though in each section there was at least something I didn’t know. For example, I never learned any of the emergency numbers here. And whenever I saw the phrase “France mêtropole” I’d translate it to “French metropolitan” in my head without knowing its second definition as “parent state of a colony.”

Reflections

As tedious as these days of slideshows and infographics were, I’m grateful the French government offered them. Or rather, required them. Maybe I’m still used to the United States form of capitalism where nothing is free, especially in terms of services. The cynical part of me thinks these courses wouldn’t exist in the U.S. because they focused in large part on government services, and we don’t have many of those.

About the author:

Gracie Bialecki is a writer and literary coach who lives in Paris, France. She is the co-founder of the storytelling series Thirst, a poetry editor at Paris Lit Up, and the author of the novel Purple Gold (ANTIBOOKCLUB).

See more about France here in the Dispatches archive.

See more Paris posts here.

Gracie Bialecki is a writer and literary coach based in Paris, France. Her work has appeared in various publications, including Catapult and Epiphany Magazine where she was a monthly columnist. Bialecki is co-founder of Thirst, a gallery and storytelling series; a poetry editor at Paris Lit Up; and the author of the novel Purple Gold (ANTIBOOKCLUB).