Expats … we’re not who you think we are.

A lot of people have commented on Dispatches’ posts and FB feed that we’re elitists … that when we say “expats,” we’re using a loaded First World conceit to describe economic migrants.

We agree.

There’s more than a little colonial baggage when we discuss “expats.” In the minds of Americans like me, the word conjures up E. M. Forster going to India, Hemingway living it up in Cuba and Karin Blixen on her coffee plantation in Kenya. Wealthy and privileged Westerners lording over the locals.

If the Indians, Cubans and Africans were going the other way, they were classified as émigrés, refugees, immigrants or (let’s say it) slaves, but not expats.

That’s so 1920.

In 2017, the question of who is an expat is both more complicated and less exotic simply because Baby Boomers are the first generation who could jump on a plane and be anywhere in the world in 36 hours.

A new generation of expats

Today, it’s all about the global mobility of talent. Probably the fastest growing expat category in the European Union is students coming from all over the world for great yet affordable educations.

Or maybe we should use “economic migrants” as so many of you have argued.

For us, that’s an overly broad classification that includes everyone from African migrants crossing the Mediterranean to Russian oligarchs holed up in Monte Carlo/Monaco. The vast majority of expats are moving around looking for economic opportunity. But it’s more nuanced than that.

Our working definition of “expat” is someone who voluntarily leaves his or her native country for a fixed period to take advantage of career opportunities. “Economic migrants” can include people forced to leave their homelands out of political necessity or lack of opportunity, with very little hope of returning … or really any desire to return.

When we first took Dispatches live in Europe in March 2016, we had an inaccurate projection of who our expat audience would be. We were thinking mostly about 40-ish corporate nomads from the U.S. and the U.K. It took a year of data to understand our expats would turn out to be much younger and more ethnically and financially diverse than we first thought.

After World War II, most “expats” were corporate nomads on limited assignments. To some extent, they’re still an important segment.

For example, my friend Bob’s wife works for one of the Eindhoven-based tech giants. She’s caught in the middle of a merger, and could end up staying here, moving to the U.S. or being assigned to China. That’s what she does.

This is the most conventional category, but it’s a shrinking one.

Data collected by various governments and the European Union institutions shows students are the fastest-growing expat category, and it somewhat skews Dispatches’ demographics, with 25-to-34 our biggest age group by far.

In 13 months here, my wife and Dispatches co-founder Cheryl have worked in Eindhoven with people from Mexico, Bulgaria, Georgia, Turkey, India, Egypt, Greece and probably a dozen other countries, and the vast majority came here as students at the Technical University of Eindhoven.

I’m going to cite data from the Netherlands, Dispatches’ headquarters, because it is the country most aggressively recruiting foreign students.

From Nuffic, the Dutch international education office:

In the 2015-2016 academic year, a total of 74,894 internationally mobile students enrolled in an accredited degree programme in public higher education in the Netherlands. This represented … the greatest absolute growth in the total number of international degree students studying in the Netherlands recorded since the 2010-2011 academic year.

It is remarkable that this growth came exclusively from research universities, where the number of international students increased from over 37,600 to just under 42,000.

In relative terms, international students now account for 10.7 percent, or more than one in ten, of all tertiary level students in the Netherlands. This share is generally much larger at the research universities (16.2 percent) and in master’s programmes (20.6 percent) than at the universities of applied sciences (7.4 percent) and in bachelor’s programmes (8.8 percent).

German students still are the largest segment. But China is No. 2.

Global War for Talent

In Europe, the people we term “expats” are hugely attractive to policymakers, and the war for talent is heating up.

Expats/highly skilled immigrants offer a solution to labor shortages in rapidly aging countries. Policymakers also believe migrants contribute “bigly,” as President Trump would say, to economic growth and boost competitiveness in the high-tech sectors.

In the United States under Trump, the prevailing “America First” anti-immigrant, anti-foreigner sentiment is aimed at Mexicans and people from Central America. But the administration has also been critical of the domestic tech sector for relying too much on international talent. (i.e., Indian and Chinese engineers and managers.)

While xenophobia is a great tool for extremist politics, the data is pretty clear: no immigrants, no economy. So, Trump has opened the door for Europe to steal America’s best talent.

If Europe does start to attract a new generation of American techpats, that could upend the global economy.

Here’s where you think I’m going to numb you with numbers. And don’t think I wouldn’t like to. I am a policy wonk. But you don’t need to deep-dive to get to the truth.

I could show you x/y graphs tracking immigration, but I rifled through some Office of Security and Co-operation in Europe and EU reports and found amazingly to-the-point numbers.

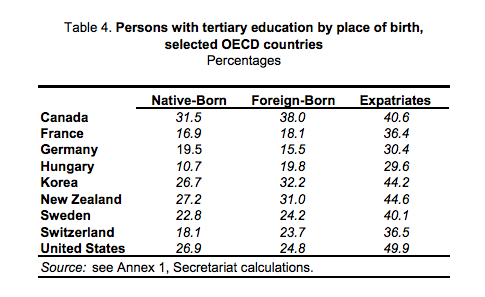

For example, expats and immigrants tend to be better educated than the natives, according to OECD research:

The New Internationally Mobile Talent

So, after looking at the data, who are the modern expats coming to innovations centers across Europe including Berlin, Amsterdam and Stockholm?

I surveyed the people I work with regularly in Eindhoven, which is one of the most international tech centers in the world.

I spoke to tech innovators and people with corporate backgrounds, and the fastest increasing national profiles here are Indians in software/IT and Chinese researchers and scientists.

In addition, Eindhoven is attracting more and more entrepreneurs from Ukraine, Bulgaria, Poland, and Eastern Europe.

Yes, this is anecdotal, but I believe accurate.

This I can tell you for certain … at this point, Americans are not a major presence in the European expat community. But here’s the thing: With the Trump administration, the expat phenom could come full circle to where we start to see top talent working in America start to leave for Europe.

Amazing facts from the International Organization of Migrants and other sources including the OSCE:

- The number of people migrating to foreign countries surged by 41 percent during a 15-year period, 2000-2015.

- The overall number of international migrants has increased in the last few years from the estimated 152 million in 1990 to 173 million in 2000 and to 244 million in the present.

- Of the annual global flow of about 15 million, most people fit into four categories: economic migrants (6 million), students (4 million), family (2 million) and refugees/asylum seekers (3 million).

- In certain host countries, such as Luxembourg, the Slovak Republic, Ireland, Mexico, the Czech Republic and to a lesser extent Switzerland and Belgium, the share of the foreign-born from other OECD countries is very high (between 65 pevcent and 85 percent), according to this report by the OECD. At the other extreme, it is close to 24 percent in Hungary, Poland and Korea and only 11 percent in Japan.

- There are 1.5 million British expats from Spain to China. Many are retirees are in Spain, Portugal, Malta, Cyprus and anywhere there’s 300 days of sunshine.

Co-CEO of Dispatches Europe. A former military reporter, I'm a serial expat who has lived in France, Turkey, Germany and the Netherlands.