Even though I tend to think of myself as a relatively adaptable person, it can get confusing sliding back and forth between my Egyptian and European lives. It is hard to describe it, but I get to the airport in Egypt and I automatically switch on the “Egypt mode.”

My body language, attitude and sense of humor, which may be seen as too crude in Europe, emerge in full.

I am sure everyone goes through something similar, more or less, be it my British friends returning home from Portugal or my French friends going home from the United Kingdom when I used to live there. However, for Egyptians – and for all those who inhabit completely different worlds – this can be extra challenging.

Managing to adapt, given how different life is, say anywhere in the Global South, to life in Europe, is not easy. I have some Egyptian friends who don’t step foot outside their homes for a few days after they arrive in Egypt because they need to re-adapt to how life in Egypt works.

The opposite of also true: The first time in Europe for any Egyptian is quite difficult on all levels.

Other expats who come from places which aren’t drastically dissimilar from their new destinations won’t be able to imagine how much adapting an Indian, an Arab or a Nigerian person has to do.

Adjusting one’s body

Something such as how one’s body is disciplined and regulated in the public space is probably a major cause for confusion. Bodies roaming the public space in Egypt (and in other parts of the world) undergo heaving disciplining.

For example, it is no secret about the level of surveillance and policing in public and private institutions in Egypt. Even walking in the street is shaped by the will to avoid trouble, not saying the wrong thing very loudly and avoiding conflicts in which the authorities could be involved.

Returning to Egypt, one is immersed once again into those modes of control and discipline. This doesn’t mean that surveillance and control don’t also exist in Europe. However, it is the switching back and forth between different modes of awareness of one’s body and physical presence as well as the degree of potential risk, which can differ massively between Europe and Egypt.

The collective and the individual

One of the things I struggled to adapt to as I lived in different countries in Europe is how individualist the local cultures can be. I know there is a common association between high individualism and freedom. I never found this association to be true, though. High individualism is capable of enslaving the individual to personal productivity as well as a cycle of goals and more goals without enjoying the enriching life which comes with a more collectivist framework.

I knew I had so much adapting to do when I called a friend crying, telling her I needed to talk. I was living somewhere in Europe at the time. My friend told me she couldn’t make time for me that day as she needed to buy a DVD.

Same call in Egypt would have ended very differently.

It is not that my friend didn’t care about me. It is just that she has been programmed to cater to her individual plans first. My biggest challenge was setting different expectations and changing my understanding of group solidarity and friendship. Over time, I also began to act differently as a friend. For example, I stopped insisting on accompanying friends to the hospital as I discovered many people don’t want you there.

The issue is that when I go back to Egypt, I need to return to turning up when my friend needs to talk, unless I have a very good, non-DVD-related reason. I also can’t skip on a hospital trip if an emergency takes place or if a procedure is going to take place. It took me a while to realize my friends in Egypt expect me to impose my company on them with all seriousness while my friends in Europe prefer it if I don’t push them.

Awareness of mortality

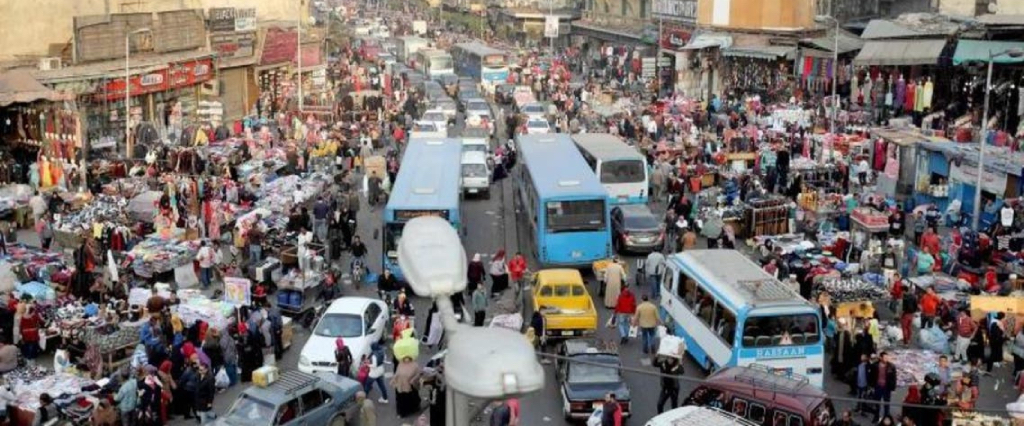

I never fully understood why tourists and visitors complained so much about the roads in Egypt until I traveled outside Egypt. It turned out that not everyone has to be that aware of their mortality every day.

I wish I could put this skill on my CV: I can cross the street in Egypt. I don’t mean to brag, but actually … I am bragging. Who wouldn’t?!

Egyptians can navigate through cars, tuk-tuks, a wandering donkey, along with some more cars and bikes coming from the opposite direction while carrying a baby, holding a toddler’s hand and talking on the phone all at the same time. A true Egyptian would do it all with a smile, ignoring all the angry car horns surrounding them. Road accidents are a common cause of death in Egypt, something people live with every day. Therefore, when I return to Lisbon and have to “wait” to cross the road, I feel a bit confused. Also, when I return to Egypt and am expected not to wait, otherwise I will never cross the road, I feel stressed.

Re-adjusting when leaving or returning home is inevitable. However, how much re-adjusting needs to be done (deliberately or as an automatic response) depends on how many worlds and lives one has and how incredibly crazy those lives can be.

Fellow expats from the Global South would relate!

––––––––––

Read more about Egypt here in Dispatches’ archives.

Sarah Nagaty has a PhD in cultural studies, She’s lived in Portugal for six years.

As a student of cultural studies, Sarah is drawn to what connects people from different backgrounds to new cultures and places, how they relate to their new surroundings and what kind of activities they could engage with in their new hometowns.